Saying goodbye to FOI

A tale of transparency

1997 was a good year for transparency. The new Labour government were ushered into Downing Street on the back of a thumping majority, brandishing a manifesto promising “open government”. What we got a year later when they fleshed it out was open governance, with an even broader based right of access, which included bodies that they thought carried out “statutory functions”. Notably, this included universities.

The Prime Minister who forced it through at the time, Sir Tony Blair, later said he regretted it; the greater transparency came at a cost of overzealous scrutiny from journalists and campaigners. In his autobiography Sir Tony said it was “like saying to someone who is hitting you over the head with a stick, ‘hey, try this instead’, and handing them a mallet”.

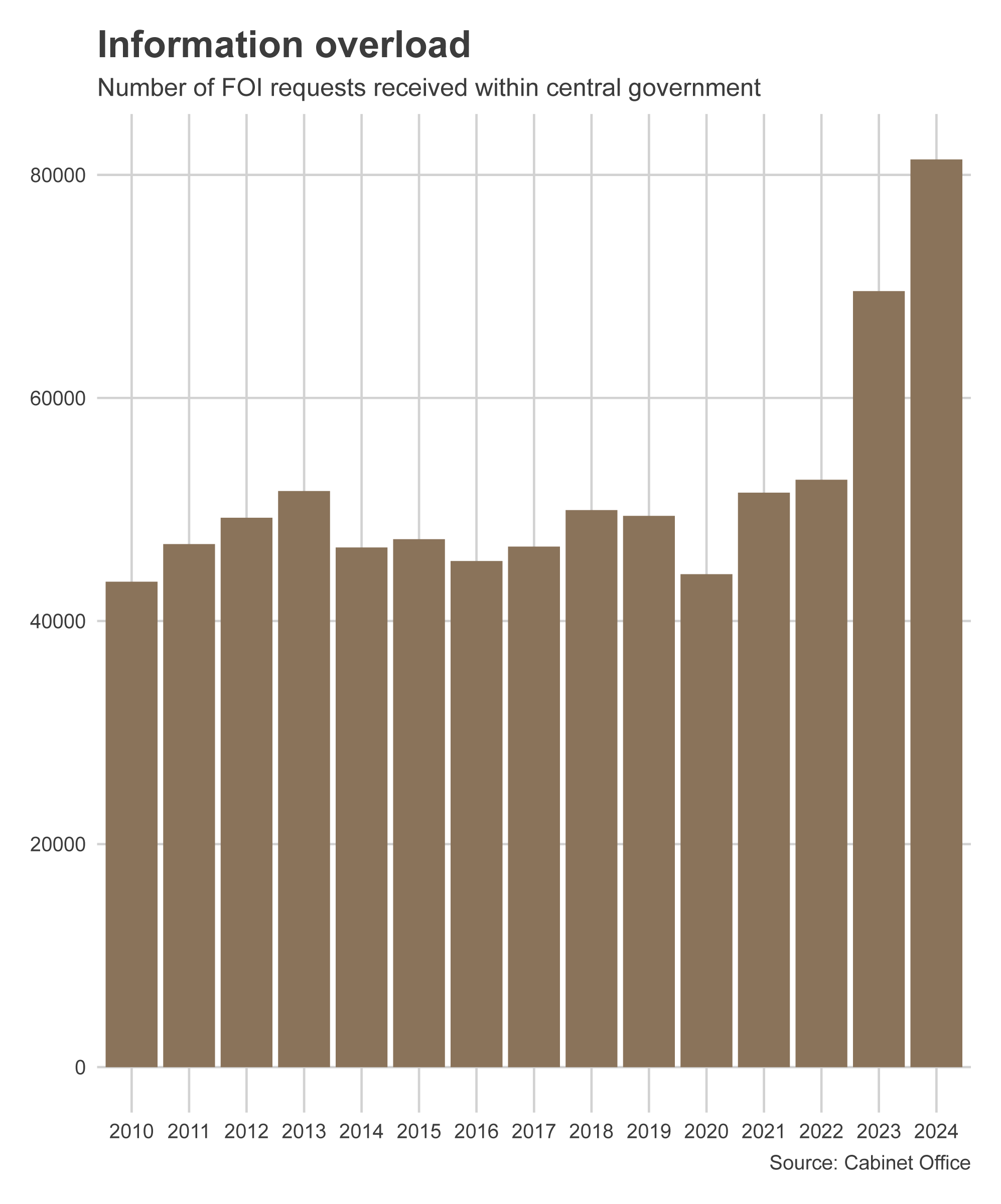

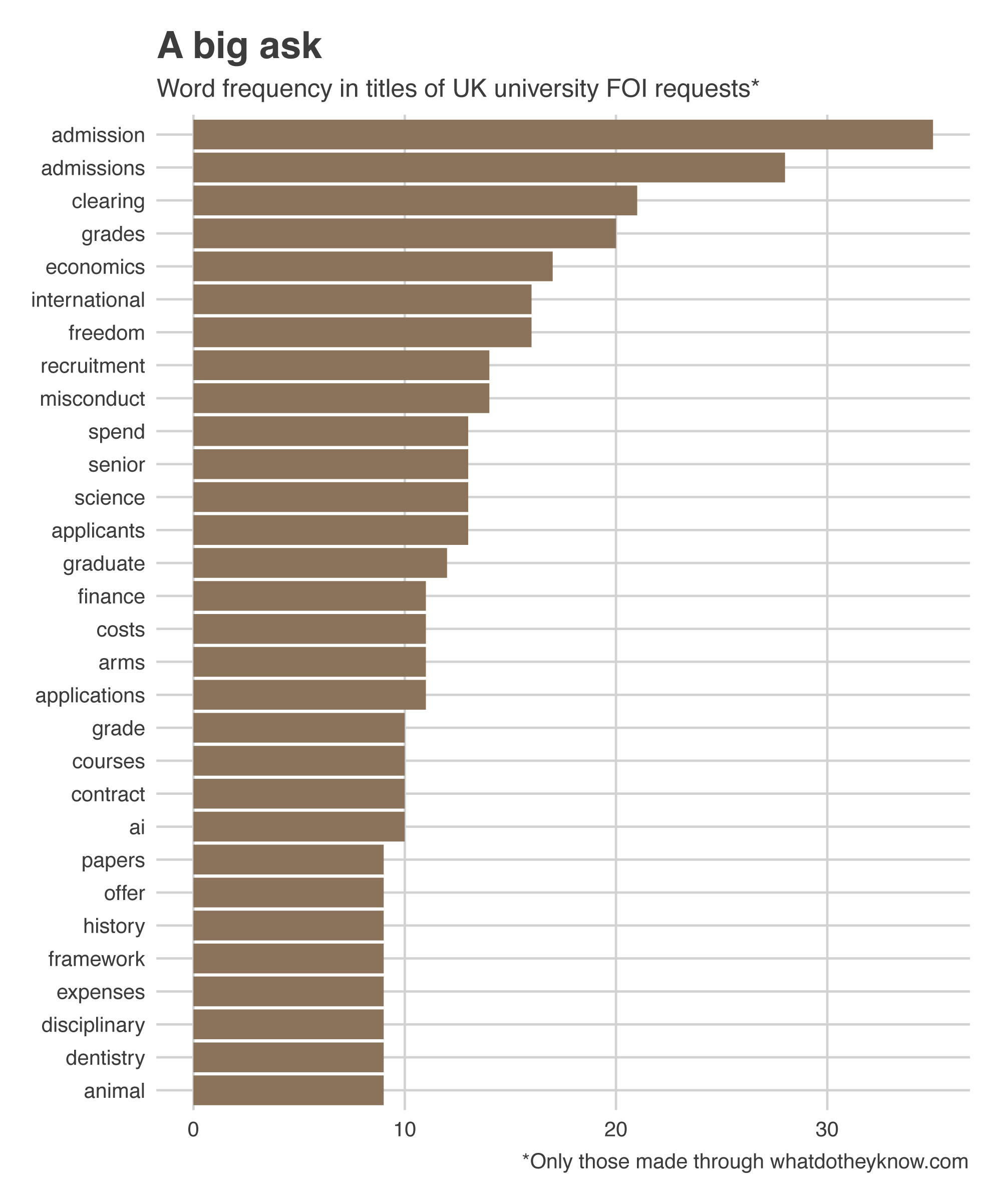

Sir Tony’s mallet has become the tool of choice for the journalist alongside activists and citizens. Although outside central government there is a dearth of FOI request data, the increase in the number of requests is striking: a 54.5% increase in the volume of requests since 2022, and a large increase in the number of requests overall (see chart).

Alongside this increase in requests comes an increase in complexity. Requests have tended to become more complex over time as the “low-hanging” fruit for information requested was made in the first few years of the act’s creation, making it harder to get an FOI that is scoop-worthy.

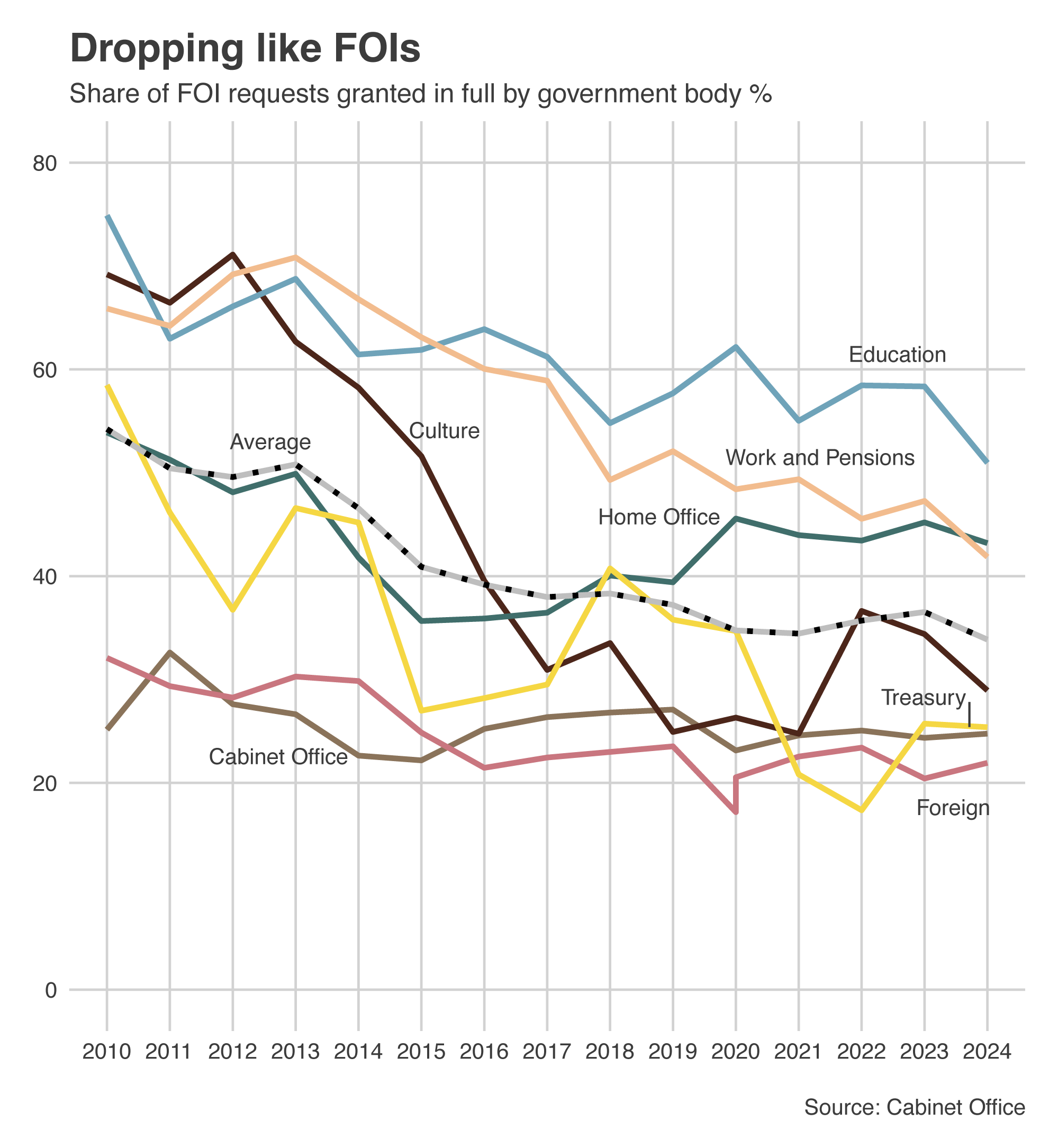

This partly explains why more requests are being turned down more often as if it were just to do with complexity, we would see more rejected on cost grounds. The Economist identified this problem in 2017. I replicate their analysis and find this situation has worsened. The percentage of total FOIs to which the government issued a respose has declined (see chart). Yet, FOIs being rejected based on cost has also declined, meaning that they are rejected based on other grounds. Comparing data from 2017 with 2023, the use of the personal information exemption (section 40) increased from 0.52% to 12.45%, owing to the implementation of General Data Protection Regulations. Information provided in confidence, law enforcement and commercial interests accounted for the the next highest increases (see this spreadsheet).

A recent paper by Jingrong Tong at Sheffield University interviewed journalists about their experiences with FOI. She tells a story of government departments deliberately restricting information to avoid embarrassment and to preserve “government secrecy”. The journalists she interviewed complained that they were forced to rely on FOIs as a substitute for what was previously sought from press officers or through relationships with members of staff. A seperate egregious example of this was when The Sunday Times attempted to get an answer from a press office over whether they were investigating an alleged investigation offence. A later FOI request showed that the press office were not keen to cooperate with the reporter: “I hate this man”, “he clearly has nothing better to be getting on with” and “just looked at [the reporter’s] Twitter” is just some of what was said in their group chats.

There are also questions over how applicant blind these requests are, as authorities are supposed to “consider FOI and EIR requests without reference to the requester’s identity or motives” in most circumstances. As George Greenwood argues on his blog, “journalists often get the feeling that their FOI is being treated differently.” Surprisingly, this also happens at the level of the student journalist, not just those on big papers. (I’ll talk about my experience shortly.)

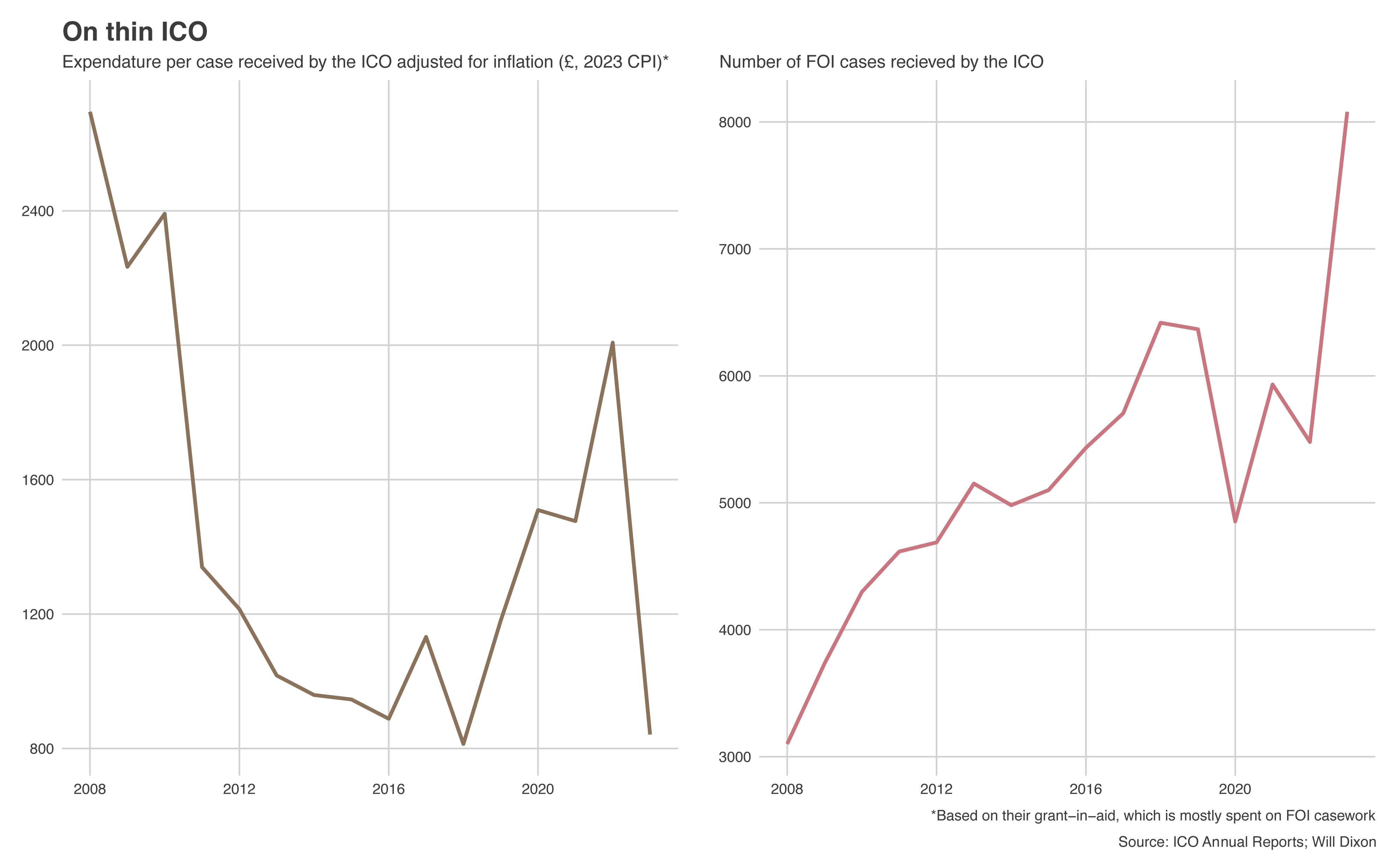

One of the key protections inserted into the act was an independent overseer. The Information Commissioner’s Office, which grew out of several pieces of data protection legislation passed in the 1980s and 1990s, was given a large amount of power to review decisions made by public bodies. Requestors can appeal to the ICO if they’re unhappy with how a public body has dealt with their request. The ICO will investigate and demand information be released, backed up with the discretionary ability to pursue cases further in the courts. Unlike the Office’s regulation of data protection, it provides this service free to the complainant and public authority, meaning the ICO is largely dependent on government funding in order to provide the service. As time has gone on, it has had to adjudicate far more cases with – in real terms – far less cash. (I used a crude calculation for this, see the ICO’s own similar calculation in a response here.)

FOI-ing higher ed

I’ve focussed on central government so far as the data for other organisations is unavailable and outdated. Local authorities tend to make up the bulk of requests according to previous studies, but they are not required to submit returns. Universities are large organisations which deal with plenty of public money but the ability to send in requests is underutilised and – as I will demonstrate from my own experience – somewhat undermined.

As a student journalist, dealing with FOI officers in universities can be frustrating, but those who are on the recieving end are often put in a tricky position by their institutions. A good paper by Daniel Swallow and Gabrielle Bourke from UCL’s Constitution Unit does a good job of explaining the difficulty of being on the receiving end of requests in a survey of university FOI officers. As one respondent put it: “Requesters think you’re trying to cover things up and colleagues think you’re too open and liberal about wanting to release information they feel goes too far or should be kept secret.” Most respondents discuss the hostility or apathy that other departments or senior executives display towards FOI law.

This dilemma is especially acute within universities. The act was built to deal with monolithic government departments that spend public money. As the representative from Universities UK argued when an Independent Commission was set up to review the act in 2016, universities are the only organisations that have to comply with FOI law that exist in an competitive environment. Therefore, unlike most public bodies, FOIs don’t just have the ability to undermine their reputation, but give their competitors an advantage. Since the act was written, universities have become increasingly detached from government as most of their income now comes from fees, not grants.

Though painful, FOI’s harsh spotlight has improved decision-making by universities, and produced a better environment for their students. Major stories, like one to do with rape and sexual assault on campus, published by The Guardian, found that universities were failing to even monitor allegations. Like other universities, Durham has since recorded all disciplinary outcomes publicly, which now encompasses sexual assault. It would have been much harder to have the same impact if FOI law didn’t exist as it makes it far easier to examine sector-wide problems.

Despite this, the bulk of FOI requests made to universities are not that hard hitting. Most people use the act for “private” reasons - to request information that is useful to them. For local authorities this might be their local bin collection or traffic policies, for universities, this encompasses students requesting admissions statistics, course information and past papers. To explore the types of requests that are generally made, I analysed the keywords from requests made on whatdotheyknow.com, an free and online FOI manager, for requests sent to organisations they tag as universities, and manually filtered them to distinguish the main subject of the request (see chart). (A loophole which allowed private companies to demand unfair access to research from higher education has since been papered over.)

Speaking from experience

I’ve written for Palatinate, Durham’s student paper, a fair amount over the past couple of years but I’ve been fustrated with their attitude to FOI. Their Information Governance Office attempted to block me and my collegues on the paper from being able to submit FOI requests and they denied that they held information until I showed them that they did. I’ve also had to ask the Information Commissioner to investigate and issue three decision notices over information they failed to disclose.

One example has been my attempt to access information to do with the finances of college Junior Common Rooms, a form of student association within Durham University’s collegiate system. On the 9th April 2024 a fellow editor submitted a FOI request to the university asking for “JCR financial reports for all available colleges for the past three academic years”. The editor followed up after 20 days and the university never responded and the editor chose not to appeal to the ICO. So, in May 2024, I submitted a similar request. I asked firstly for the funding that the University gave to JCRs. They took 32 days to respond to my request, and even then they didn’t provide it. I appealed showing that college accounts contained money from the University in an internal review, at which point they gave me that information.

Then, when I sent another request asking for full JCR accounts, they again failed to respond on time. I sent a reminder after 20 days, to which they apologised. Ten days later I reminded them again and they said they would conduct an internal review which would take 20 days. They emailed me before that new deadline to tell me that they would be late. When they finally got back to me on 23rd October they refused my request on cost grounds, despite me showing them evidence that they responded to the same request for information three years prior. The ICO issued a decision notice in my favour on 12th March. They said that “the University’s response concentrates mainly on the resource constraints it was operating under, rather than an analysis of why the request would exceed the cost limit.” On 10th April, the University finally released the information that had originally been asked for in April the year prior (an article based on this is due out next month; see the correspondence here).

This is just one example. I’ve had to take to the ICO several times over finances and gender divides within departments, winning both times at the expense of having to wait months for a resolution. With the gender divide documents, the university argued that it would undermine their ability to recruit and retain staff. Even after the ICO’s decision notice, the University requested an extension, giving themselves a further 40 days to release information that they confirmed they already held.

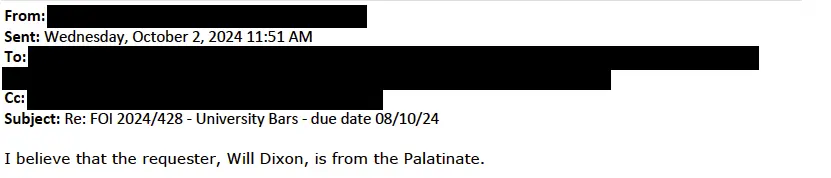

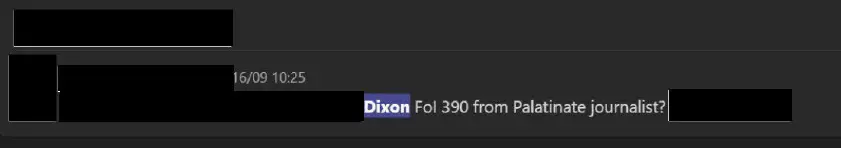

I had begun to think that the University were treating me differently because I was a student journalist. On 14th October I got an email from Durham’s Information Governance team saying in response to a request: “We have received a number of requests for information from Palatinate members, unfortunately due to the high volume of these requests and the burden it has placed on certain functions in the University, we have concluded that we need to process all requests from Palatinate members as being received from one requester.”

Essentially they took requests that asked for different things from different people, and said it constituted one request which was over the cost limit. They made clear that any request received “within a 60 working day period” would not be responded to. We were able to account for some of the seven requests as coming from student journalists, but not all. I also asked them to internally review how they had misapplied the Commissioner’s guidance over aggregating requests. They issued me with a 1,370 word review in which they claimed that they had grouped the information based on it being “student and college data”. All I wanted was access to details to do with college residence and data for an article to do with Durham’s drinking culture on the sale of alcohol within University bars – two requests that had been submitted in as many months.

I also asked them how they had decided that the requests were coming from people working in concert. They said that the “outcome of the supply of information to the requestors are articles in the Palatinate student newspaper, so from the point of view of the public authority it was receiving a large volume of requests from the same entity”. They also said that they’d done something similar before when receiving a lot of requests from the paper, saying that they would deem them vexatious if it wasn’t for the “important journalistic function” that the paper carries out. They promised that they would provide me with “general advice … on approaches to future requests”. I am yet to receive this although I have not yet chased it.

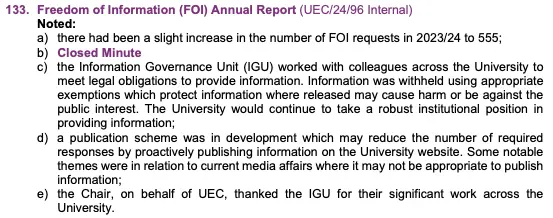

This unfortunately applied to some previous members of Palatinate, some of whom are employed by national newspapers, some of whom work freelance. None of which can be at all construed as working in concert. They claimed that people affiliated with the paper “have submitted 57 requests since June 2024. This accounts for approximately 20% of all the requests the University received during this time.” To the universities’ main decision making body, they said that there had been a “slight increase” in requests over the period that I sent many of my requests, although one of the minutes was closed to me so I can’t be completely sure what was said.

In addition, on the advice of a journalist with experience with FOIs, I submitted a subject access request to see if they were treating my requests blindly. What I got back was three heavily redacted screenshots showing that they were discussing my affiliation to Palatinate months before they decided to try and cut off my ability to send FOI requests.

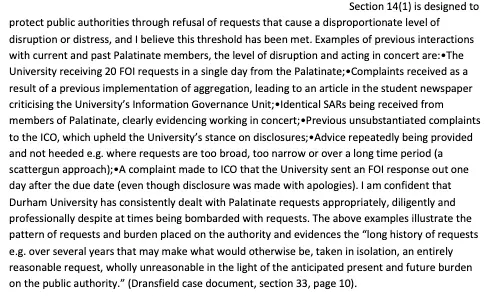

I sent a further FOI request based on this to read what had been redacted, but they rejected it based on it being “vexatious”. They said that the request lacked “public interest or serious purpose coupled with the volume of Freedom of Information requests and other individual access requests from the requester and their colleagues”. They wrote another 1,000 words in response to my subsequent request for an internal review, where they claimed again that the paper was one requestor and that “since 2021, the University has received 400 requests from the Palatinate”. Although they admitted the request would “not itself impose a significant burden on the University”, they also outlined some of the ways that the paper had caused the Information Governance team distress (see screenshot). It is currently being decided on by the ICO, I will update this post when I hear back.

I have continued to submit FOI requests for stories. Each time they would threaten me that they would cut off my access to information if I continued to make requests. I kept going and remain quite proud of the articles (1, 2, 3 among others) that I wrote as a result, as well as a couple that remain in the works.

FOIs, applied

In a book by Matt Burgess, his advice on how a journalist should approach an FOI request is particularly helpful. The idea that journalists get lazy and send in complex requests on a punt is true – I know I’ve sent in requests on a whim – it is a waste of time for the officer on the other end to deal with them.

There are plenty of good guides on how to submit FOI request, but must also consider: should I send a request. I think you should only send in FOI requests if you say no to the following:

- Can I find the information elsewhere?

- Are they likely to have the information?

- Is the information frivolous?

Really do answer these questions properly. Do a proper Google search. Read through boring reports and other secondary literature, for instance the dataset that I produced from ICO statistics came partly from the 2016 review and partly from their own annual returns over the last few years, I didn’t request the information from them as it was already published. Do not use FOI officers like librarians, they aren’t supposed to spend hours doing your work for you.

To figure out if they hold information, ask people, think about what they collect online forms on, read minutes and reports. For finances, think about how they will set their budget, and how they are structured as an institution. And, above all, make sure that you are asking the right organisation, What Do They Know maintain a useful database.

And, although the example I have outlined above with Durham might be on the more extreme side of compliance, generally the people you are speaking to want to help you access the information, they are just prevented from doing so by either their colleagues or the difficulty in getting hold of information in the way that you have requested it. Be willing to rephrase, resubmit and reduce down your request, especially on the back of advice that you give them. Practically, it is far quicker to resubmit a request than wait for a judgement from the ICO.

I hope this proves helpful. There are plenty of ways that FOI law in Britain can be improved, but used well, it can be a real force for good. Use it.

Find the replication data and documents to accompany this blog post here and here