Rail: fare competition?

Lumo train passing Nether Poppleton – DS Pugh/Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Lumo train passing Nether Poppleton – DS Pugh/Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Travellers looking up at the departure boards in London’s Kings Cross will see several companies running trains to the same places.

This marks a new trend. As the government press ahead with their plans to consolidate Britain’s privately run franchises into one state-run behemoth, Great British Railways (GBR), private firms are looking to diversify away from franchises by petitioning the state to run competitor services.

Dubbed open access agreements, private operators bid to run trains in timetable lulls between franchised services. For passenger services, they are the only way firms can reap the potential rewards of competition. (Since the pandemic the government has absorbed the risk of franchises.)

Open access agreements were baked into the law when then railways were privatised in 1993. Almost all freight services are run on the model; the first to carry passengers, Hull Trains, started in 1999, aiming to compete with the incumbent East Coast operator’s one train per day to the city. It now operates seven trains per day from Hull, a poor northern city on the east coast, with above average satisfaction and reliability.

A couple of other firms have attempted to replicate this success. Grand Central run their trains to some of northern England’s smaller cities, and Lumo rivals airlines running between London and Edinburgh. Long distance fares may be 10% more expensive in real-terms than in 2004, yet on the East Coast, where competition is more fierce, prices have increased more slowly.

Labour have so far paid lip service to retaining open access operators. Present plans for GBR give it the power to decide which open access operators are allowed on the network. This will likely snuff out new applicants. Currently, applications are currently assessed by the Office for Rail and Road (ORR), a regulator. In the decade before April 2025, they approved half of the ten applications that were made. On the latest batch of applications this year, the Department for Transport opposed all but one application. Even then they offered lukewarm support.

A new governing body is unlikely to want to give up some of its timetable to a competitor. Even the benefits of centralising the timetable are unlikely to be realised; Labour may be hell bent on controlling passenger rail, but they are happy to leave freight to the private market, which still needs timetabling.

For now, only one more operator looks set to join the open access ranks, running slots on the West Coast mainline by the end of the year. Three others have been approved but work has not started; many of the routes that the ORR give access to never have trains running. Congestion is also an issue. The ORR rejected three different proposals on the West Coast on July 3rd, fretting that there wasn’t enough slack in the timetable. Still, seven applications across the network are still awaiting decision, a record number.

Heidi Alexander, the Transport Secretary has sent repeated letters to the ORR, expressing her worries that open access services will steal passengers that would otherwise travel on franchised routes. The RMT, a union, argue that open access operators should be should be folded into GBR.

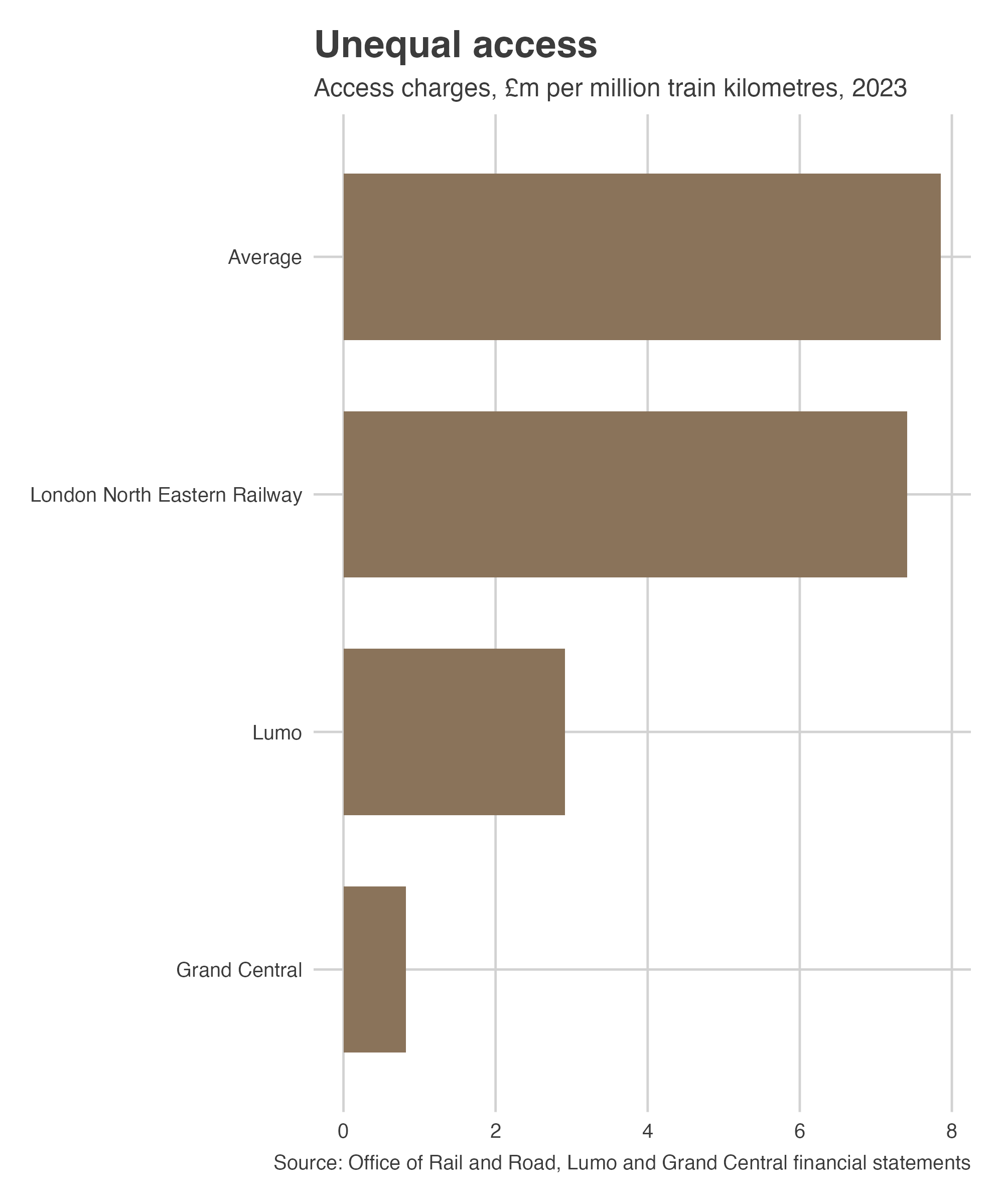

They are right to be concerned. Britain’s rail subsidy has increased by 65% since 2022. Instead of blocking access, Ms Alexander should level the playing field. Open access firms were for a long time exempt from paying fixed charges to maintain the railways, tantamount to an indirect subsidy (see chart). Phill Wheat of the University of Leeds and his coauthors found this is partly why their fares are cheaper. The Competition and Markets Authority, a regulator, called for a levelling of the playing field in 2016. And, although the ORR has introduced a new fee in order to mitigate this, it targets firms that they think can eat into their profits – so far this only includes Lumo. They could gradually introduce a charge to all operators.

The ability to tap into excess capacity on the railways should be celebrated. Bradford, a city of half a million, had no trains to London before Grand Central begun operating four per day from 2010. Approve more trains and passengers will come.