You wouldn't download a dinosaur

Scroll through Thingiverse, a library of 3D printable models, and it resembles an e-commerce site. In place of a purchase button, consumers can instead download digital instructions for a three-dimensional (3D) printer.

3D printing makes solid objects by adding—rather than subtracting—material. Printers work like a pâtissier with a piping bag, producing objects layer by layer, albeit with more precise control and with materials like concrete, metal and plastic.

Polls show consumers know what 3D printers are but take-up is low. They find the complexity of the software needed to run it off-putting. Some firms have managed to simplify their software, but without a trained eye, printers often malfunction. Maintenance instructions can be complex and poorly documented.

AI could soon help. Some show promise in troubleshooting mangled prints—one uses ChatGPT to adjust printer settings on the fly. Others assist with initial designs, generating models that are either imprecise, impossible to print, or both.

Still, the market for printers is expected to double in size by 2030, according to Mordor Intelligence, a market research firm. In 2023, the sales of paper printers were 21m against 2.7m sales of 3D printers. Internet searches for them are also on the rise. Over the last five years entry-level prices have decreased threefold, with Chinese startups like Bambu Lab and Creality producing good printers for sub-$300.

Printers are useful in other markets. Most defence and aerospace firms 3D print some of their components. In the construction sector, one estimate by Tongji University claims 3D printing concrete structures could eliminate “one-third to half” of costs. Thousands of homes have already been printed—a huge labour saver in a notoriously inefficient sector. In May, a huge 3D printer piped out a Texan Starbucks.

Doctors print patient scans to practice on, with dental braces, hearing aids and prosthetics having been printed for decades. Researchers are able print a new organ out of cells from a simple swab, or a tablet with a custom formulation in the lab.

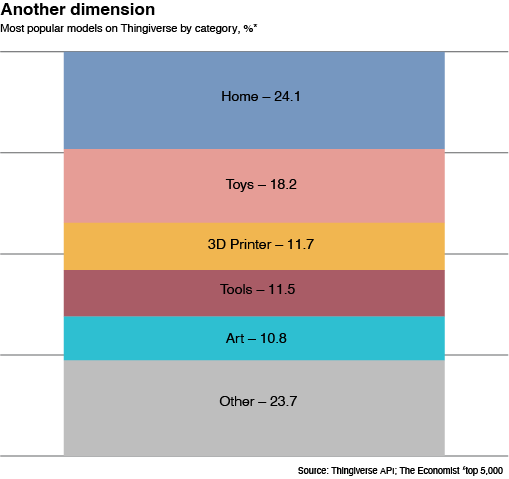

Much like how the home printer did not eliminate the market for producing books, larger and more complex goods that benefit from economies of scale will remain mass produced. Models tend to be less than the size of a tissue box, and suited to certain niches (see chart). Like print-on-demand book services, more localised print “farms” may crop up for larger or more complex models with lower demand.

Consumer 3D printers excel at certain applications. They make cheaper toys, tools and spare parts than mass produced equivalents. Research by Joshua Pearce of Western University and his co-authors shows that 3D-printed toys are 75% cheaper than their Amazon equivalents. Another study printed a comparable $5 Rubik’s Cube for $0.29 worth of plastic. Recently, Bambu Lab trained an AI model that can create simple and unique figurines from a prompt.

Printed spare parts can also cut waste and save money. Philips, an electronics firm, posts printable fixes compatible with its line of toothbrushes and razors online. For other repairs, helpful hobbyists fill the gaps. In the future, AI tools could create printable fixes based on 3D scans from a consumers smartphone. This is a problem for model floggers: copying digital files is far easier than with physical goods.

3D printed goods can also be customised. Thingiverse lists around 60 prints compatible with the popular Billy bookcase sold by IKEA. Earlier this month, Hugo Boss, a designer brand, released a shoe printed on demand, fitted to each customer. MIT have built an AI model which can customise models without losing its function. It might not be long before a model’s answer could be a 3D one.

You can download my replication code on my GitHub.