Why Indian opinion polling is often wrong

Voters standing in a queue for their turn to cast votes at a polling booth of Kalyan Puri, in Delhi — Sanjiv Misra / Photo Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India (GODL Licence)

Voters standing in a queue for their turn to cast votes at a polling booth of Kalyan Puri, in Delhi — Sanjiv Misra / Photo Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India (GODL Licence)

“It’s a graveyard,” said Yashwant Deshmukh, the director of C-Voter, one of India’s biggest political pollsters. He says he is lacking competition. It is not because his polling is accurate.

Good political pollsters are thin on the ground in India. Polls have existed since the 1950s and became mainstream in the 1980s. As television took off within the country in the 1990s, so did political polling, and it was reasonably accurate. At the same time, foreign firms moved in but have shied away from published opinion polls in recent years.

Pollsters say that the media in India, which is diffuse, are not willing to pay for good polling. Some cheap out on inexperienced operators. Parijat Chakraborty, a senior executive at Ipsos India, said smaller pollsters “try to get some visibility, some saliency, at the cost of money, at the cost of accuracy”. Ipsos India now focusses on private polls.

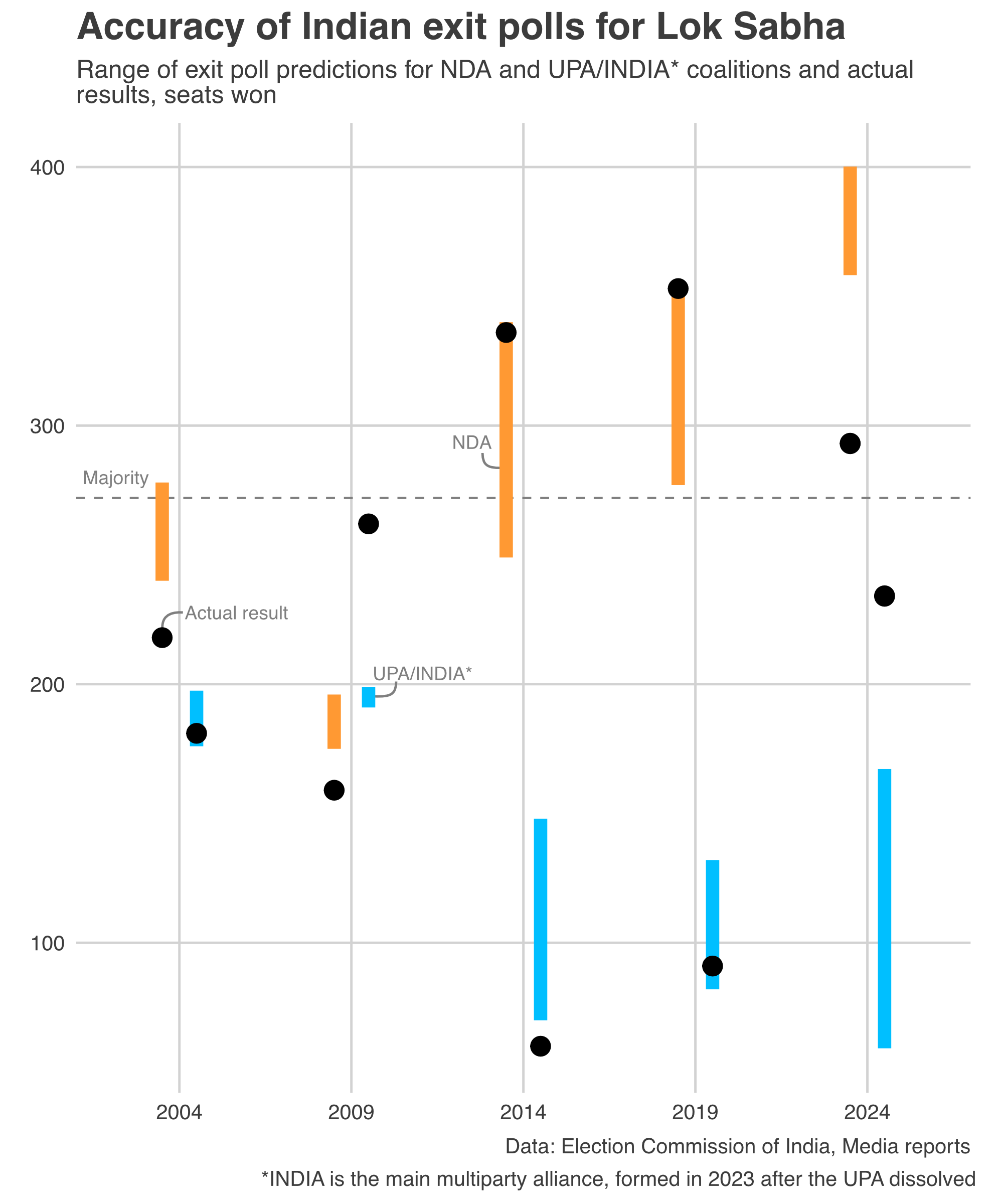

Firms continuing to poll for the Indian press have been dented by inaccurate predictions. In 2004, pollsters got the winner wrong in an infamous miss. Despite this, polls still hold the power to move markets. In 2024, when exit polls predicted a sweeping victory for the ruling BJP, Indian stocks rallied, before tumbling once results made clear the party’s majority had slimmed. The director of Axis My India, broke down on television afterwards.

Polling companies are trying to self-regulate and many are members of the Market Research Society of India, which has a code of conduct. And, outlets which publish polls are supposed to follow new Press Council of India guidelines which demand information on methodology. An idea to create an Indian Polling Council was floated in 2015 to investigate industry-wide misses. According to Deshmukh, it exists as an “informal grouping of all serious pollsters” within a WhatsApp group. Chakraborty would prefer more jointly commissioned polls.

The problem is uniquely Indian. Polls tend to underestimate the rural vote and lower caste, which both turned against the BJP in 2024. This has partly left pollsters open to claims of colluding with the BJP, especially as the party commissions private polling from them. They also rely heavily on fieldwork, and increasingly on telephone consultations. C-Voter’s researchers speak 11 languages but the country speaks 780. “You get a low response rate among the females, lesser educated, among the minorities”, Deshmukh explained. He does some fieldwork to reach the many rural voters without phone signal. CNX, another pollster, tries to sample specific minority groups. Marginalised groups are hard to poll, and uniquely for India, hard to identify. There has not been a caste census since 1931; CNX said they sink “significant resources” to develop their own data on caste. For all pollsters, few polls means fewer opportunities to course-correct if their sample is wrong.

A particularly tricky problem is converting the vote shares into seat share, which is a near random guess in India’s voting system. “There’s no direct correlation”, explained Deshmukh, “everybody uses their own formula”. CSDS, the oldest Indian polling agency, does not publish seat shares. Most others would prefer not to, but for their clients.

Thank you to Parijat Chakraborty, Yashwant Deshmukh, and Bhawesh Jha for agreeing to be interviewed for this article.